Cheryl and Jerrold Bisera of Newbury Park traveled to Lahaina, Maui, in August to scatter Jerrold’s father’s ashes near Lahainaluna High School, the elder Bisera’s alma mater. Twenty-four hours later, Lahaina itself lay in ashes, the Biseras’ family members were fleeing the disaster zone, and an aunt had been lost to the flames.

“We had no idea that tragedy was unfolding before our eyes,” Cheryl told the Guardian.

The Bisera family — siblings Joey of Camarillo, Julie Feinstein of Newbury Park and Jerrold of Newbury Park, plus spouses and other family members — converged in Lahaina in early August to honor their father Jose’s wishes that his ashes be spread below the “L” on the hill above where he graduated. Jose had grown up in the family house at the old Pioneer Mill camp near the iconic smokestack. His father was an immigrant from the Philippines who worked at the mill. The house, which Jose rebuilt in the 1970s, served as a multigenerational gathering place for decades until it was sold in 2020.

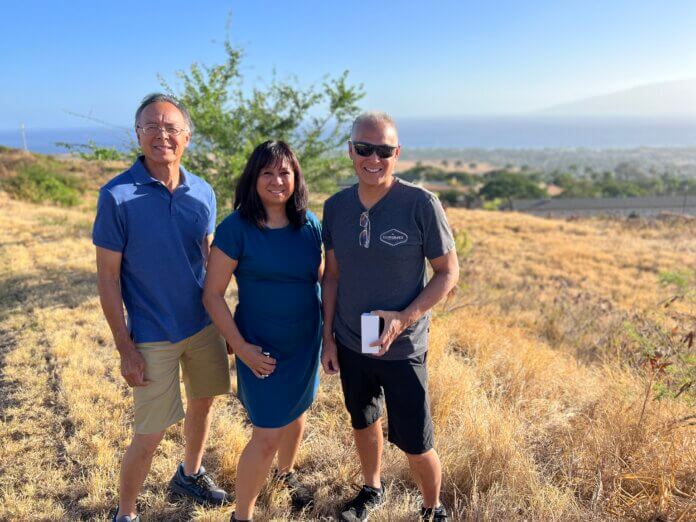

Cheryl and Jerrold arrived in Lahaina in early August, drove by the old house and the historic smokestack to take photos, and later went downtown to visit his cousin at Kimo’s restaurant, where she worked. On Monday, August 7, family members all met and drove up the hillside near Lahainaluna High School to spread some ashes of their father and mother, Violet. (A portion of her ashes were also spread in Hilo, on the Big Island, where she grew up on a sugar cane plantation camp home. Most of Jose’s and Violet’s ashes are buried at Conejo Mountain Memorial Park in Camarillo.)

“We held hands in a circle and said a prayer,” Cheryl recalls. “We gave thanks for their lives and reflected on their sacrifice. I was weepy. It was sunset. We were going to meet for dinner but instead just went our own ways. We were too big a party for a reservation.”

None knew that disaster was just ahead and would unfold with little to no access to real-time information.

Overnight winds were powerful enough to wake them up, and by the next morning, there was no electricity. The couple had stocked their condo in Napili Bay with food and, fortuitously, filled up the gas tank of their rental car the night before. Their phones were charged, and Cheryl had made plenty of ice to keep the food cold as they ventured to the beach and elsewhere. Cell service was still available, so Jerrold checked them into their flight for the next day.

For the first time, they heard about a brush fire in Lahaina that the news said was contained. With electricity out and gas stations and restaurants closed, the Biseras stayed local, “rekindling old memories from before we had kids,” she says. They walked through the Hyatt resort, which was functioning on generators.

“Everything was calm,” Cheryl says. “One of their restaurants was open. We walked up the beach, and it was extremely windy with huge gusts that sandblasted you.”

Wandering into the Westin pool area, they ran into Jerrold’s cousin from Sacramento and learned that cell service was now mostly down, Uber had stopped functioning, and tourists were lining up for food at the few open restaurants down in Lahaina that morning.

“It was starting to get that emergency feeling,” she says, but “we had no idea that such a horrific tragedy was about to take place.”

At around 5:45 p.m., the Biseras saw smoke coming from Lahaina.

“Wow, that brush fire’s still going,” they said. After dinner, the glow on the horizon had intensified, but because there was no cell service and no Internet access, they continued to believe it was contained and not a threat.

“We had no idea his aunt was dying in that fire,” Cheryl says.

While they walked on the north end of Napili Bay to get a better view from the elevated lobby of a resort at about 7:45 p.m., an employee there was cracking light sticks and putting them on the steps. He said traffic was not being allowed to pass through Lahaina, and some houses had burned.

“We had no idea that such a horrific tragedy was about to take place.”

“That was the first we were hearing that something sad was happening,” Cheryl says.

Unsure how they would reach the airport, the couple got up early the next morning and packed the car with their luggage, bottled water and food on ice. On the highway toward Lahaina, people were standing on the roadside, trying to capture cell signals. Cars began turning around.

“You have to go all the way around the backside of the island,” a police officer told the Biseras, and so they ventured northeast on the beautiful but treacherous cliffside road, which in many places was just one car wide.

“It was a big sigh of relief once we made it around and into town and got cell coverage,” Cheryl says. “Again, we had no idea of the catastrophe that had just happened.”

Before their midafternoon flight, they did some last-minute shopping and “noticed a lot of people at Walmart,” she says. “I asked an employee, and she said it was because of the fires.”

By this time, fifteen or so of the Biseras’ own family members were displaced, and some would lose their homes — but with a near-total shutdown of communication on the island, nobody knew. Meanwhile, the Biseras drove up and down the parking lot, praying to find someone who needed their extra supplies. Spotting a woman with a baby, Cheryl felt a prompting and jumped out to offer her food, water and ice.

“Yes. I’m staying in a shelter,” the young lady replied. “I’m waiting to find out if my house burned down. My sister is with us, and her house burned down.”

The airport was not overly busy as the Biseras seemed to be “one step ahead of the catastrophe,” Cheryl says. Some families had slept there, some had slept in their cars, and some had been separated from belongings left in now-unreachable condos and hotels. Some didn’t even have identification.

Arriving late in SoCal, Cheryl and Jerrold learned of the extent of the damage — and the loss their family suffered — the next morning at home in Newbury Park.

“We started to consume all the news and the images in the Twitter videos, watching the horrors unfold and reaching out to relatives there,” she says. “They were waiting to find out if any of their homes had been spared.”

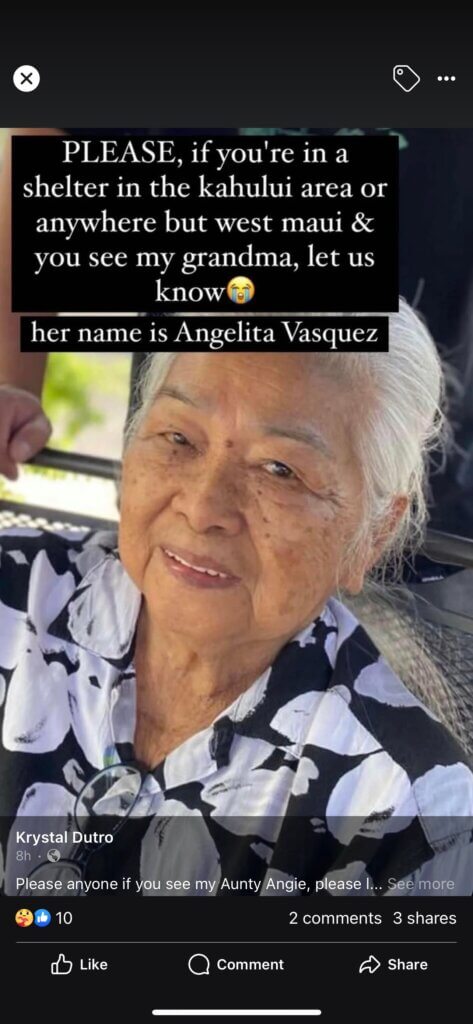

A few days later, Jerrold’s Auntie Angelita Vazquez was confirmed by DNA matching to have died near her unit at a senior housing complex in Lahaina. Her son, who was living with her, had tried to reach and rescue her but was overcome by smoke and had to shelter at the nearby middle school. One of the cousins later went to the residence and said, “I was not prepared for what I saw … nothing but ashes.”

Miraculously, two of the cousins’ homes were spared while surrounding homes burned down. As for the old family home near the smokestack, it, like most everything else in Lahaina, is completely gone.

Somehow, Lahainaluna — the oldest high school west of the Rockies and the place where some of Jose’s ashes were scattered — escaped all damage, perhaps because of its elevated position on the hillside.

As the Biseras sort through what happened, they say vague official timelines have hindered their understanding of how and when things took place.

“We find it very frustrating as we are trying to reconcile what we saw with what was happening,” Cheryl says.

Jerrold says, “Being personally touched by catastrophe is surreal because we were right there looking at the smoke and glow, and yet unaware of the suffering. Where our immigrant family story begins and was still being lived out is literally in ruins.”

All sympathy should go toward those who suffered great loss, including Jerrold’s cousins and their families, says Cheryl. “They lost their matriarch, their mother, their grandmother and great-grandmother. She was the last living sibling of Jose.”

At the moment, the extended family on Maui “is just trying to find their footing,” say the Biseras. Some have lost jobs; others are working while grappling with tremendous grief and loss. One cousin is housing sixteen relatives in a small home, while news reports say FEMA workers are staying in five-star resorts.

“The people of Lahaina and those housing them in surrounding areas deserve our help right now,” says Cheryl.

The Biseras suggest donating to organizations comprised of locals helping locals who are doing work on the island to help survivors. These include:

Citizen Church Maui (citizenchurchmaui.com, citizen.church/relief), located just north of Lahaina town, distributes essentials with the help of Convoy of Hope and Mercy Chefs.

Upcountry Strong (upcountrystrong.org, [email protected]) is a nonprofit helping the poor in Upcountry Maui.

King’s Cathedral Assembly of God (kingscathedral.com), the largest church and church network in Hawaii, works with CityServe and other organizations to give away hundreds of thousands of meals, plus provides clothing and shelter to needy locals.