Pioneer missionary and U.S. Army Ranger veteran Dave Eubank regularly visits the Conejo Valley to speak at churches and spend time with friends. Eubank leads a trained army of humanitarians and fighters in Burma called the Free Burma Rangers (FBR). They conduct operations to save innocent people caught in the crossfire of the country’s vicious, seemingly endless civil war. Eubank employs skills from his time with the Army Rangers to lead troops on long jungle hikes up and over muddy mountains, often within earshot of gunfire and artillery.

The Conejo Guardian’s Kate Kilpatrick caught up with Eubank after his recent visit. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Conejo Guardian: You’re equipping the locals to fight and defend and to preach the gospel to their own people.

Eubank: Yes. The fighting part, we don’t do that much of ‘cause that’s not our main job. We’re not against it, but our role is helping people and getting the news out. … Usually, we don’t have enough weapons to face thousands of Burma army with helicopters and jets and armored vehicles. So we do very little fighting, but we’re not pacifists. We will if we have to, and so we’re training people to, number one, look to God. Number two, share what Jesus has done for them. Number three, give humanitarian care for people in need. Number four, tell the story of what’s happening.

Conejo Guardian: I’m curious what a day with the Free Burma Rangers looks like.

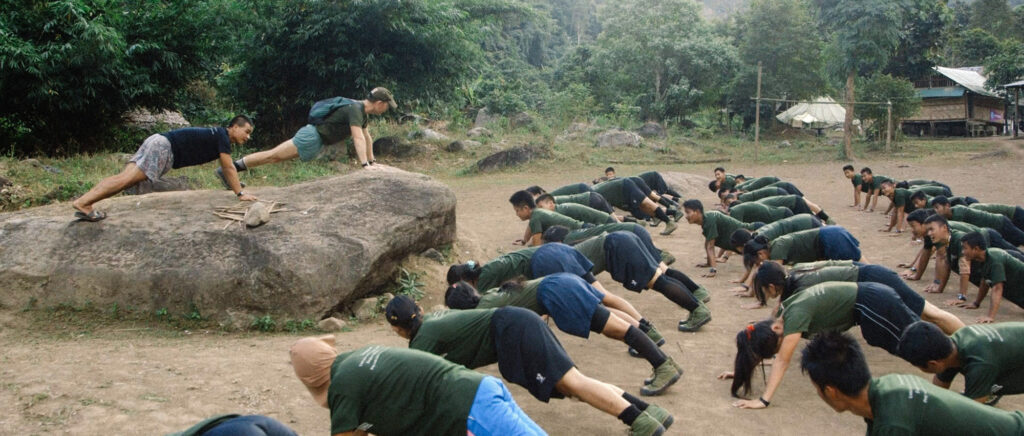

Eubank: A typical day in training starts about 4:30 or 5:00 in the morning with wake up, reveille, then running and calisthenics and push-ups and sit-ups and more running around in the dark until the sun rises.

Then morning work until around 6:00 or 6:30. Then jump in the river, take a bath, go to breakfast, come back for morning devotions around 8:30. Then classes start at 9:30. Classes could be in a bamboo-and-wood house or a big classroom. Classes taught by our own ethnic people in the Burmese language would be land navigation, or medical, or dental, or emergency transport, map reading, or compass reading, or use of videography, camera use, rappelling, swimming, horse-packing, a variety of skills they need to function in war zones.

Afternoon is more personal training, more running up and down mountains. You’ve just got to be fit to get places and carry all your gear. At night, maybe it’s night land navigation and night swimming, whatever. That goes on for three months until they graduate.

Once they go on mission, a typical day is walk 10 miles, or 15, or 20, or 25, or sometimes 30. Just brutal in the mountains. It’s not like walking on a normal California trail. It’s going through thick jungle, up and down, stepping over trees and logs, and carrying all your gear on your back with medical and other supplies on the horses behind you, going into a village that’s been burned. They’re not there anymore. Documenting the burning, finding the survivors the next mountain over, setting up a little clinic under the trees, a dental clinic under the trees, running our kids’ program to motivate the kids, like a big outdoor Sunday school in the jungle of their hiding place. Treating wounded, interviewing people, “Hey, how’d your village get burned? What Burma army did it?” Writing a report. Stay with them a couple of days. Coordinate for more supplies to come to them. Let’s say they need tarps and school supplies ’cause they can’t go back to their village before school starts next week, so they need six huge plastic tarps, 500 notebooks and a thousand pens. We radio that out, and it’s carried in. Maybe take two weeks.

Then we go to the next place. And that’s kind of a typical day. If you’re a medic, you’re with patients all day. If you’re a Good Life club counselor, you’re singing songs to the kids all day, starting in the morning with worship and skits and funny things, games and snacks and more games. Then more skits about Jesus. Then gifts for the teachers and school supplies we give to the kids. We carry all this in on our backs or on mules and horses. In some areas of Burma that are more developed, we can use trucks, but mostly we’re on foot.

At, say, 4:00 or 5:00 in the afternoon, we walk downstream, then take a bath, wash the clothes, hang them around the fire, sit around the fire and eat dinner. Go to sleep in a hammock. It’s like super-camping with a purpose. The next day, go to the next place.

Conejo Guardian: Wow. What are the responses of the people you help?

Eubank: First, they’re scared, like, Who are you? Most people know us now, but sometimes all they see [are] forms moving through the jungle and are like, “Is that the Burma army?” Once they realize it’s you, they’re so happy you’re there. They can tell you all their problems and where the sickest people are and who needs help. They’re very grateful. They say things like, “God sent you. We prayed and prayed, and look, God answered our prayers. You’ve come. And please don’t leave us. Please tell the world what’s happening.”

Conejo Guardian: Was going to Burma always the plan for you?

Eubank: It was not the plan. I grew up overseas in Thailand as a missionary kid. I went to school at Texas A&M, was commissioned out of the Army there as an officer, served almost ten years in the Rangers and special forces, and got out to go to seminary.

A tribe in Burma came to Thailand, met my parents, who were still missionaries there and said, “Our people are warrior people, and they need Jesus. Your son is a warrior” because they knew I was in special forces. “Have him come share about Jesus.” This was the Wa tribe of Burma, a small tribe that used to be headhunters — a pretty tough tribe in Northern Burma. So I said yes and asked Karen to marry me, and she said yes. We got married in Malibu, California, at Leo Carrillo State Park, right on the water. Then our honeymoon was to Thailand and then Burma.

We started working with the Wa tribe and then the Karen [sounds like Kuh-RIN] tribe, and that’s a bigger minority group. Burma, by then, had been in 73 years of civil war. We were right in the middle of it. So that’s how we got started, by invitation of the people there and by the doors God opened for us to get there.

Conejo Guardian: Was it an easy choice? How long did it take you to say yes?

Eubank: A couple seconds. I didn’t even know what it was.

Conejo Guardian: You ask the Lord about everything?

Eubank: Well, it’s the best way. Life is full of challenges and enemies and injustices. If you read the 23rd Psalm, David talks about walking beside still waters, laying down in green pastures, walking on paths of righteousness, then all of a sudden, he’s going through the valley of the shadow of death. Why? Well, that’s the only way I can get to the place I need to get. He gets through the valley of death by leaning on God and has this abundant table, his head’s anointed with oil, his cup runs over, but it’s in the presence of the enemy.

For all of us, we may not be interested in Satan. We may not be interested in sin, we may not be interested in war, we may not be interested in hate — but it’s interested in us, and it’s going to come. We’re all in a battle. All of us. It doesn’t matter our occupation. The first place the battle starts is in our hearts. You have to choose to be about God’s kingdom or Satan’s kingdom, and there’s no middle ground.

Right away, we started the Free Burma Rangers as a response to the fighting we saw. But the Free Burma Rangers only was a maximum of twenty of us, young men and women, mostly men, helping at the front lines people under attack. But by the year 2000, the ethnic resistance in Burma — there are many tribes against the government — and the ethnic leaders said, “We want teams like you’ve got — holistic, humanitarian, spiritual teams that follow God, love each other, help people right in the fighting areas, aren’t too afraid and get the news out and have all these skills. Can you train them?” That was the big change. We prayed about it and said yes. And then we started training. We trained more than 6,000 young people in Burma. We’ve trained probably 500 teams. We have 120 teams active right now.

In the middle of that, in 2014, we were invited to Sudan in the Nuba Mountains, where there was heavy fighting. We took a team from Burma to Sudan to help twice. There was a cease-fire, and right after that cease-fire, ISIS was doing its attacks in Iraq and Syria, where we were asked to help them. We started in 2015 working in Iraq and Syria, where we still work today. We’ve got a team in Iraq. We’ve got a team in Syria. When Afghanistan fell last year, we went to help, and now we have a partnership with a part-time team of Tajik Christians on the Tajikistan/Afghan border helping Afghans.

Conejo Guardian: What are some of the stories that have stuck with you or your kids over the years? I’m also curious about what it’s like raising kids in that environment.

Eubank: They all grew up there. My son is 16; my daughters are 20 and 22. Now they’re at Texas A&M University … studying nursing and veterinary medicine, but all their school breaks are with us in Burma. So they might end up with us in ministry. I don’t know. I hope so. But my main hope is that they do what God has for them.

When we went to Sudan, we got bombed every day, and my kids and wife were with the people, the Sudanese, hiding in the caves, sharing with them. My daughter Suzanne said, “Daddy, we’re not just a family; we’re a team.” So we’re bound, first of all, by love as a family, by love of God together, and also by the gratitude we have to be a family and a team and part of the Rangers.

It’s really fun, and we are deeper and deeper together. We do everything together that we can. We like each other. To people under attack, when they see kids show up, it’s an instantly calming effect. The people in Iraq said, “You must think God loves Americans and Iraqis equally because your kids are here with our kids.” Or, like the Kurdish leader said, “You brought your son, your most precious thing. I give you my most precious thing — my country.”

Conejo Guardian: Is there anything else you’d like to mention that would be important in getting a picture of Free Burma Rangers?

Eubank: When Afghanistan fell in 2021, I met the acting president, and we were able to help many Afghans escape and survive across borders in Tajikistan. This acting president said, “Americans, it’s not your fault Afghanistan fell. It’s the Afghans’ fault and the fault of countries such as Pakistan and others. You Americans are guilty of cowardice and ineptitude the way you got out of the country, the whole airfield debacle. Yes, you should be ashamed of it, but get over it. You were never better than us, but you are different. You care about doing the right thing. God has blessed you as a country, so just say you’re sorry for what you did and get over it because we need you to keep leading. For your sakes and for the world’s sake, we need America to lead because Americans do care. There’s a heart of love across America that cares about others, and we need that in the world, so please keep being a leader. If you give your leadership to Russia or China, do you think they’re going to care? No. Nobody’s perfect, but you do care. That’s why we want you to lead, so keep leading.” That’s one message I’d like to get to your readers.