How did America get its name? Before 1507, the world was thought to consist of the continents of Europe, Africa and Asia. This belief dated back to the second century A.D. and the works of the Egyptian geographer Claudius Ptolemy. Then, in 1492, Christopher Columbus made his voyage across the Atlantic Ocean and made landfall in the Western Hemisphere. However, Columbus believed he had landed in Asia, and the recognition that there was a separate continent between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was not immediately understood.

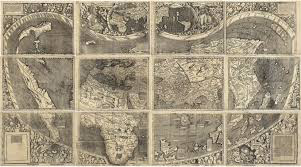

In 1507, a German cartographer named Martin Waldseemüller began work on a new map that radically changed most people’s perception of the world. Operating in Saint-Die, France, Waldseemüller and his colleagues, including a German scholar and poet named Matthias Ringmann, published a book called the Cosmographiae Introductio (Introduction to Cosmography). The book declared that the known parts of the world had been joined by another. The author states:

“These parts have in fact now been more widely explored, and a fourth part has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci (as will be heard in what follows). Since both Asia and Africa received their names from women, I do not see why anyone should rightly prevent this [new part] from being called Amerigen – the land of Amerigo, as it were – or America, after its discoverer, Americus, a man of perceptive character.”

Thus, America is named after the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci.

Why Vespucci and not Columbus or another explorer? Vespucci made at least two and as many as four voyages across the Atlantic between 1497 and 1504 and apparently ventured into what is now South America. Vespucci documented his travels and published a report entitled Mundus Novus (New World), where he declared that a previously undiscovered continent surrounded by water on both sides existed in the Western Hemisphere.

Although Waldseemüller and his colleagues knew about Columbus’ voyage, it was understood at the time that Columbus had discovered another part of Asia, not a new continent. Also, Vespucci traveled south in areas that went beyond the known world, as described by Ptolemy. Waldseemüller concluded that Vespucci was the first to discover this new part of the world. Thus, it would be named for Vespucci. Had Columbus understood he found a new continent and written about it, we could be living in the United States of Columbia or another similar-sounding name.

Oddly, subsequent maps created by Waldseemüller omitted the term America or showed the continent surrounded by water on both sides. This has confused scholars ever since. It is believed that the politics of the time, mainly between the exploring nations of Spain and Portugal, explain this. Creating a map with new territory likely created tension over who controlled the new land. Spain, which financed Columbus’ voyage in 1492, would not recognize the name America or put it on any maps for more than two centuries, believing that Columbus was being denied his place in history. It is possible that Waldseemüller took the name “America” off his maps to appease Spain.

History took care of this naming problem. In 1538, the most influential cartographer of the age, Gerardus Mercator, put the names “North America” and “South America” on one of his maps.

Another aspect of Waldseemüller’s 1507 map that confuses scholars today is how accurately South America is drawn. Vasco Nunez de Balboa is the European credited with discovering the Pacific Ocean in 1513. Ferdinand Magellan did not round the tip of South America until 1520. At some important points in the map, the width of South America is within 70 miles of accuracy. Given what Waldseemüller had to work with in 1507, there appears to be more to the story. However, the answer seems lost to history.

One thousand copies of the Waldseemüller Map were printed in 1507, a large number for the time. For hundreds of years, no known copy of the map seemed to have survived. Then, in 1901, a priest and professor of history and geography named Father Joseph Fischer was invited to examine a collection of maps and books at the Wolfegg Castle in southern Germany. It was here that the first known surviving copy of the Waldseemüller Map was discovered.

After negotiations with the Wolfegg Castle owners and the German government, the Library of Congress purchased the map for $10 million in 2003. In 2007, it went on permanent display at the Library of Congress in an exhibit titled “Exploring the Early Americas,” an important piece of history for all Americans, showing in earliest printed form how our country got its name.

Steve Villalobos is a Southern California professional who holds an undergraduate degree in American History and political science. He is also a contributor and writer for 1776history.com.