For Americans, World War II is fast becoming a distant memory from the textbooks of school classrooms. Very few people are left with first-hand remembrance of the patriotism that mobilized thousands to do whatever they could to fight for freedom.

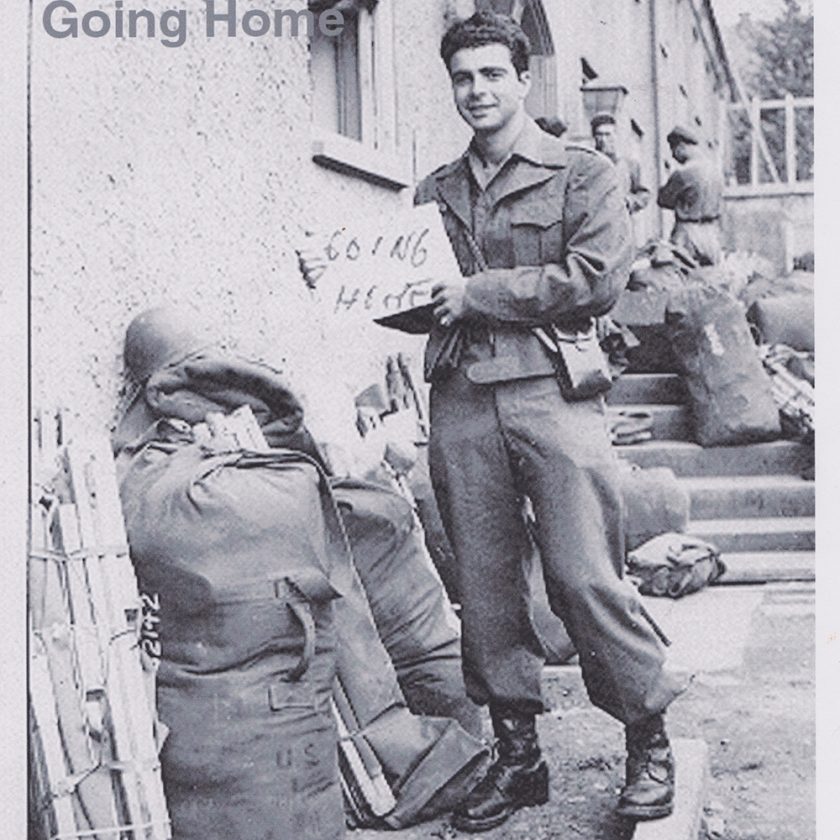

Leonard Zerlin doesn’t need a textbook because he lived through those pages of history. In fact, he has photo albums of archival pictures that he personally took during his time in the military…images of everything from daily life to the horrible realities of war’s devastation that capture a time of distant memory.

It was a time of a world torn apart by evil, a story of tragedy and triumph. It is a story that, over four years, turned an 18-year-old boy into an old man.

A week before the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Leonard Zerlin was graduating high school and looking toward a future full of possibilities. However, that fateful day marked a pivotal moment that would change his perspective on life forever.

Reading about what was happening in his grandfather’s Jewish newspaper, he determined to help those who were having their personhood and human rights ripped from them. So he enlisted in the United States Army and began the intense training. Reflecting on the grueling and punishing nature of that time, he says it tested the men’s willingness to conform to a strict system.

“The purpose of boot training, or basic training, for the Army is the fact you lose your identity as a person,” Zerlin said, “because you have to conform to things that you find objectionable like, uh, waking up at 3 o’clock or 4 o’clock in the morning and getting out of a warm cot with 20 other guys, and getting on your hands and knees to pick up cigarette butts for two hours.”

It’s the culture they had to learn to live with. According to Zerlin, the purpose of this was to infuriate them so that their anger would fuel a collective bond amongst each other. In retrospect, it made him appreciate that he was part of something bigger than himself.

“It changes you; you learn to adapt to live with all cultures and adapt to their personalities,” he said. “And you don’t forget that your life might have to depend on them as well.”

Boot training only lasted six weeks, but Zerlin stayed on American soil for a year and a half before ever going overseas. While the preparation was necessary, Zerlin still felt like he was wasting time when thousands were dying in battle. One of the hardest realities was seeing many of his friends killed due to crashes and accidents from the intensity of the training. His friends’ lives were being lost, and they weren’t even fighting in the war yet. It took an emotional toll on him, as he realized that any of those deaths could have easily been him.

However, while others were happy to stay on American soil where there was more comfort and less danger. He desperately wanted to know he was making a difference. Zerlin’s spirit wasn’t at ease, and his conviction kept him focused on the goal of one day fighting for his country.

In 1943, he was given his chance. Traveling aboard a ship, he arrived in Scotland in the middle of the night. He then boarded a train where he remembers watching all of the lights in the windows go by and thinking about the people who lived there. Through four years, their backyards had been a war ground, and it suddenly became very real to Zerlin. No longer were these just names printed on the pages of his grandfather’s newspapers. They were actual people, and this was a matter of life and death.

As the lights in the windows faded from view, Zerlin took in the solemnity of the moment.

“I’m finally here,” he said. “I’m finally here. This is my new home. Whether I come back, I don’t know.”

Thus began his time of deployment. He was placed in the Air Force as a turret gunner on a B-26 bomber, playing an integral role in historical missions like the D-Day invasions on the Normandy beaches. He personally witnessed the devastation of Nazi concentration camps, encountered many near-death experiences, and even earned a Silver Star Medal for his exceptional bravery in combat. Despite the harrowing stories that make him an American war hero in most people’s eyes, Leonard doesn’t see himself that way. He says he just did what needed to be done to protect the lives of others.

Following the end of World War II, Zerlin was discharged from the military on November 11, 1945, and went on to live a relatively normal life. He married and raised two kids while working for a variety of aerospace companies, retiring around the time when space-age technology and home computers started developing.

After retiring he took up many hobbies such as biking, skiing, tennis, sculpting, clock making, woodworking, and photography. Throughout all this time, he never spoke much about what transpired during his time in the war.

His daughter, Ellen Jirari, talked about her father’s humble spirit and said that his generation is “not the kind of men that boast about what they had done and their accomplishments in the military, you know. It’s just a generation that we will never see again. They just don’t make men like that anymore.”

It had been almost 50 years since the war ended when Zerlin says his high-school-age granddaughter came to him asking for help on a school assignment.

“She used to visit me every Friday night,” he said. “We talked of her boyfriends and school, and Grandpa was here to listen to her stories. And she says, ‘Grandpa, I have to write an article about World War II. Tell me about World War II. I think you were in the service. I see airplanes hanging from the ceiling.’”

After asking her some questions, Zerlin says he was shocked by the lack of American history being taught. Although his granddaughter was an “A” student, she didn’t understand many key facts and significant dates of World War II such as who the President was at the time, who America was fighting, or how the war even started.

Zerlin handed her his photo album and told her to ask any questions she had.

As she pored through the pages of the album, one picture, in particular, caught her eye.

It was an image of nine people taken at Zerlin’s airfield near the town of Sainte Mère Eglise. Zerlin had been stationed there shortly after the D-Day invasions.

Zerlin explained that he had been the first American to visit their farmhouse after four years of Nazi occupation. Needing some fresh eggs and bread, he decided to ask if these strangers would trade their products for some sugar, candy, sweets, and coffee. After numerous visits, they formed a friendship and ultimately became like his adoptive family. The young girls even taught him a little French. Zerlin invited them to visit his airfield, and that’s where the picture had been taken.

He can’t remember most of their names except for one he calls “Momma Olga.” She was a displaced person, having been hired by the French family to take charge of the cooking and cleaning after escaping from another occupied German country.

She became like a second mom to him and gave him a St. Christopher’s medal of safe passage that he wore with his dog tags all through the war. He believes that the medal may have helped him survive.

After telling his granddaughter this story, he says she was fascinated and said, “Let’s write them!’”

Zerlin thought that would be a waste of time. After all, it was almost 50 years ago, and he had no idea how to even begin contacting anyone. Regardless, his daughter took the pictures, made prints, and had his letter translated into French. That letter was then sent off to the Mayor of Sainte Mère Eglise and printed in newspapers all over France looking for a “Momma Olga.”

Upon receiving his letter, the secretary of the mayor was startled to see two of her aunts pictured in the photo as teenagers. She called her cousin, Liliane Guerrier, and showed her the picture of her mom as a young girl. Through this connection, Liliane and her husband Gilbert decided to try and help Zerlin find this “Momma Olga.”

“I completely forgot about the letter,” Zerlin said. “I thought it’s a wasteful letter…Six weeks later, I get a big envelope embossed with the name of the mayor of Sainte Mère Eglise. They were so thrilled—they were so thrilled to make contact with this young soldier from 50 years earlier.”

Although Momma Olga wasn’t found, the friendship between Zerlin and the Guerriers continued long after they gave up looking. Today, they consider each other best friends, regularly emailing back and forth, celebrating each other’s birthdays, and continuing a connection of friendship that was planted over 75 years prior.

“They’re the most delightful, loving people,” Zerlin said.

They have even come and visited Zerlin at his residence in Thousand Oaks. While Zerlin has never been back to France, three younger generations of Zerlins have been welcomed into the Guerriers’ home and been given a tour of Sainte Mère Eglise and the surrounding areas, reliving some of his experiences in the war.

His daughter describes how beautiful and emotional that was for her to see the very beaches that her dad fought on, his airfield, and the cemeteries of fallen soldiers.

“For miles you see crosses and a few stars and each one represents a death, a life that was there defending our freedom,” she said.

When she called him back in the States, Zerlin said she was crying. The experiences of what these people endured for four years and what this war meant for so many, including her father, became reality. She is so thankful that her dad is still alive.

“How lucky we are to live in these times where we take our freedoms so for granted,” Jirari said.

Zerlin, now 96 years of age, has lived through almost a century and jokingly self proclaims himself as an “antique.” During that time he has seen sixteen Presidents hold office. In a time when America is arguably facing some of the most polarizing times in our over 200-year history, Zerlin has hope for healing and overcoming the current political turmoil.

“When I speak to my grandkids, I say the main thing in a marriage is compromise,” he said. “You’ll get people, the same family being diametrically opposed to something, right? Well, we have the same thing with our country. But don’t forget the beauty of America is diversity.”

Through Zerlin sharing his story with his family, it led to a connection that transcended time and space, culture and history, young and old generations, and resulted in a friendship that continues to this day. The conversation with his granddaughter prompted him to start sharing his story with schools and universities, educating the next generation about World War II. Today, he has written multiple books about his experiences in the war, has turned his bedroom into a museum filled with memorabilia, and hopes that his contributions will help to keep this important time period alive in the minds of Americans.

In a final email, Zerlin expressed this sentiment:

“Life is measured by your legacy, not by riches, but by love and affection, and guidance. I am thankful for my almost 97 years, still writing books and printing pictures.”

Note: If you are interested in finding out more about Leonard Zerlin or the personal experiences of men in World War II, you can check out his book World War II Memories on Amazon.